It all began in 1587 when more than a hundred English colonists landed on Roanoke Island, off the coast of what is now North Carolina. This would have been the first permanent English settlement in the New World had they not mysteriously disappeared in the years after their arrival. Historians, archaeologists, and other experts researched and speculated for years, with no conclusive evidence as to what happened to all those people.

The mystery inspired theories ranging from the outlandish — colonists resorting to cannibalism, or experiencing a zombie apocalypse — to the mundane but more plausible — being attacked by Native Americans, facing disease, or simply assimilating into Native American tribes and leaving their original settlement. This latest theory gained more traction in 2020.

The “Lost Colony” was made up of mostly middle-class people from London, one of explorer Sir Walter Raleigh’s attempts to colonize North Carolina. They had a difficult first few months on the island and their leader, John White, left for England to request more supplies and manpower. He left behind his wife, his daughter, and his newborn granddaughter Virginia Dare, who would have been the first English child born on those shores. But his return to England coincided with the outbreak of war with Spain, when Queen Elizabeth I called on every available ship face the Spanish Armada.

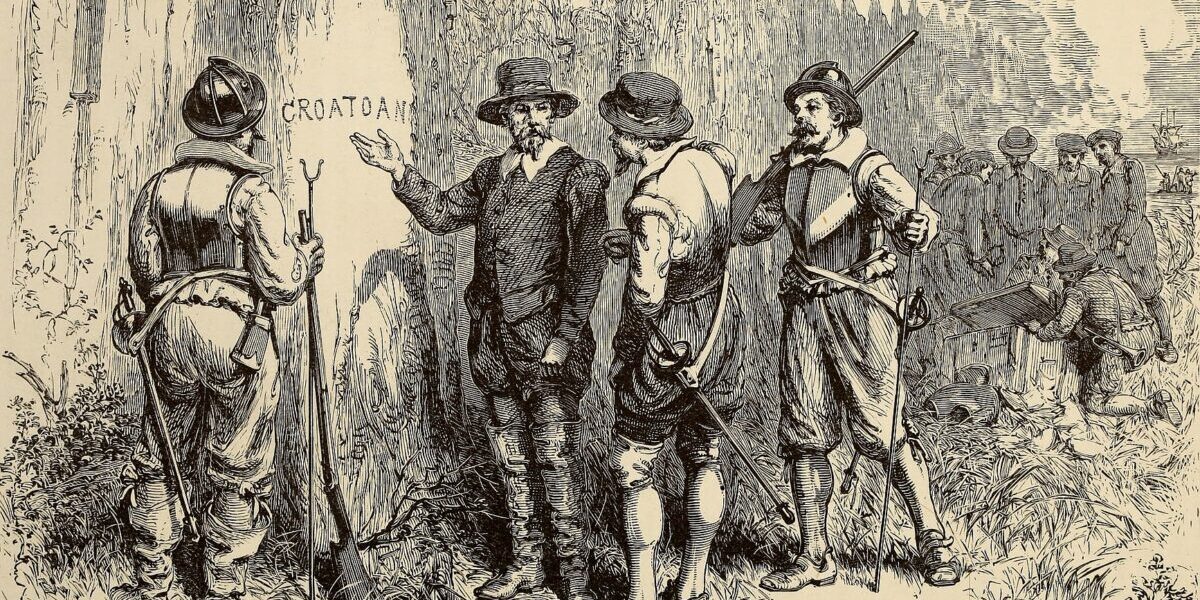

White finally returned to Roanoke in 1590, nearly three years after they landed, and was confronted with an abandoned colony, with no indication of what happened there that resulted in the disappearance of more than a hundred people. The only clues remaining were the letters “CRO” carved into a tree and the word “CROATOAN” carved into a wooden post.

Andrew Lawler, author of “The Secret Token: Myth, Obsession, and the Search for the Lost Colony of Roanoke” told Discover Magazine that “It looked like the colonists had left in an orderly manner.” There were no signs of a massacre, or any human remains.

“Croatoan” was the name of a neighboring island, and the name of a Native American tribe residing there, presently known as Hatteras Island. White tried to make the expedition 50 miles south to the island but a lack of provisions hampered his plans. He went back to England to get help from Sir Walter Raleigh — their colony’s wealthy patron — only to find Raleigh was organizing a new venture in Ireland. Without the funding White could never go back to investigate further.

The colony did not appear to have been forgotten after White failed to muster the resources for another search. According to the National Parks Service:

Twice in 1604 George Waymouth presented versions of a treatise called “The Jewell of Artes” to the king. It assumed that the lost colonists had been found and could be reinforced. Waymouth led an American expedition but it went far to the north of Roanoke. The play “Eastward Hoe,” by George Chapman, Ben Jonson, and John Marston, produced in London in 1604, refers to colonists left in America. Its production implies that a broadside about the colony had recently been printed. Christopher Newport returned from a Caribbean voyage in 1604, on which he may well have reconnoitered the route to the Chesapeake. (In 1607 he reached that area with no trouble.)

In 1604 prisoners captured by the Spanish in St. Helena Sound on the Castor and Pollux said that their expedition, while French, had an English captain, John Jerome of Plymouth. This commercial venture had been instructed to call at Croatoan, but Jerome was killed and the ship captured before the expedition reached the Outer Banks.

In 1607, when the English established their first permanent settlement at Jamestown, they were well aware that a colony had been left on Roanoke Island twenty years earlier. The Jamestown colonists made several attempts to find the lost colonists; and investigated Indian reports of Europeans living at various locations; but no survivors ever surfaced. The fate of the lost colonists remains one of the great mysteries of American history.

What are the more believable theories?

One of the most interesting clues emerged in 2012 when the British Museum analyzed White’s coastal maps for the First Colony Foundation, a research nonprofit. 21st-century imaging techniques showed hidden markings in the form of a four-pointed blue and red star, indicating an inland fort where the colonists may have resettled after leaving the coast. The markings were possibly made using invisible ink, presumably to protect the locations of colonists from the Spanish. White himself made an oblique reference to this site when testifying about it after he tried to return to the colony.

This evidence expanded upon the theory that the colonists had moved 50 miles inland. James Horn, a historian with the foundation, had written a book hypothesizing that some of the settlers may have moved there to an area he called “Site X.” Nicholas M. Luccketti, an archeologist and his colleague at First Colony Foundation, said the colonists could have split up, with some ending up at Site X, and some on Hatteras island. In 2012, a number of colonial artifacts emerged from an excavation, but there was no sign of a fort. Site X has not been excavated since 2018 but Horn believes the search for evidence will continue.

The June 2020 book “The Lost Colony and Hatteras Island” looked into a decade of excavations that had taken place on Hatteras island. Scott Dawson, a researcher there and the author of the book, argued that the colonists were taken in by the natives on the island, as evidenced by historical artifacts there.

Native American author Maynor Lowery, who wrote the 2018 book “Lumbee Indians: An American Struggle,” made a similar argument, saying they had been absorbed in by the tribes. The Lumbee people were descendants of a number of tribes from across a wide area, including the eastern region of North Carolina. “The Indians of Roanoke, Croatoan, Secotan and other villages had no reason to make enemies of the colonists. Instead, they probably made them kin,” she argued. She added that the whole premise that assumed the colony was lost implied that Native people had disappeared too, “which we didn’t.”

Horn disagreed, arguing that while many experts over the last 50 years thought Hatteras was a destination for the colonists, it was still unlikely that all of the colonists ended up there. Dennis Blanton, an archaeologist at James Madison University, argued that taking in all 100 people would have been a significant strain on a tribe’s resources, and such sheltering would have been “limited.”

Mark Horton, an archaeologist at the University of Bristol, investigated Hatteras island with Dawson, and argued that was where the colonists went, while admitting there was no “smoking gun,” but everything in context pointed to it.

Some have searched out DNA evidence of the colonists assimilating into Native American tribes. In 1701, explorer John Lawson visited the region and heard some Hatteras Indians claiming their ancestors were white people, and he assumed the lost English people “conform’d themselves to the manners of their Indian relations.”

For around a decade, computer scientist Roberta Estes was trying to find genetic evidence confirming the above theory, through the Lost Colony Family DNA Project, but has not found conclusive evidence. In a 2009 paper with the Journal of Genetic Geneology, Estes said that the Lumbee people had long claimed descent from the Lost Colony “via their oral history,” which specifically involved Virginia Dare, the first English baby born on the New World. Extracting DNA samples from 16th century bones taken from Site X, Roanoke Island, and Hatteras and comparing them to current-day eastern North Carolinian descendants could give answers, but getting that material has been elusive.

She detailed her struggle for clues in a long post on her website in 2018, and concluded:

Today, the Lost Colony DNA projects will continue to build membership, waiting on that break we need. I’m hopeful with every new person that joins the Y DNA project that they are the one!

I anticipate that English records will continue to be transcribed and be added to online databases, becoming accessible to everyone through services like Ancestry, MyHeritage and FindMyPast which focuses exclusively on British and Irish genealogy.

Identifying the colonists and their families in England remains the key to solving the mystery of the fate of the Lost Colony. Those records won’t do it alone, but without that information to use in order to track descendants forward in time, at least today, we probably can’t solve the mystery.

However, there is one possibility. Given that the colonist surnames are reported among the Lumbee, it’s possible that the Y DNA of those families could point the way back to their English roots. That road sign just might tell us exactly where to look in England for those missing records, which of course might lead us right to the colonists themselves.

Is this wishful thinking? Of course, but it’s also possible.

There are so many theories about what happened to the so-called “Lost Colony” some more plausible than others, and with many leads discovered through modern technology and expertise. But with no conclusive answer yet, the search continues.

Sources:

Cascone, Sarah. “Archaeologists May Have Finally Solved the Mystery of the Disappearance of Roanoke’s Lost Colony.” Artnet News, 6 Nov. 2020, https://ift.tt/1mz9CSO. Accessed on 3 Dec. 2021.

Emery, Theo. “Map’s Hidden Marks Illuminate and Deepen Mystery of Lost Colony.” The New York Times, 4 May 2012. NYTimes.com, https://ift.tt/BQ6MFRs. Accessed on 3 Dec. 2021.

Emery, Theo. “The Roanoke Island Colony: Lost, and Found?” The New York Times, 10 Aug. 2015. NYTimes.com, https://ift.tt/FOUYLn3. Accessed on 3 Dec. 2021.

Estes, Roberta. “The Lost Colony of Roanoke: Did They Survive? – National Geographic, Archaeology, Historical Records and DNA.” DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy, 28 June 2018, https://ift.tt/sSCAELM. Accessed on 3 Dec. 2021.

Estes, Roberta. “Where Have All the Indians Gone? Native American Eastern Seaboard Dispersal, Geneology and DNA in Relation to Sir Walter Raleigh’s Lost Colony of Roanoke.” Journal of Genetic Geneology, 2009, https://ift.tt/O8jRYAS. Accessed on 3 Dec. 2021.

“Have We Found the Lost Colony of Roanoke Island?” National Geographic, 9 Dec. 2013, https://ift.tt/ElHMg3F. Accessed on 3 Dec. 2021.

“Newfound Survivor Camp May Explain Fate of the Famed Lost Colony of Roanoke.” National Geographic, 5 Nov. 2020, https://ift.tt/E0r1jhq. Accessed on 3 Dec. 2021.

“Search for the Lost Colony.” Fort Raleigh National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service). https://ift.tt/Jux5mvO. Accessed 3 Dec. 2021.

“The Lingering Mystery Behind the Lost Roanoke Colony.” Discover Magazine, 16 Nov. 2021, https://ift.tt/SpcNZGm. Accessed 3 Dec. 2021.

“The Lost Colony of Roanoke.” Britannica. https://ift.tt/L3nR1TY. Accessed 3 Dec. 2021.

“The Search for the Lost Colony of Roanoke.” National Geographic, 29 May 2018, https://ift.tt/GXbTymR.

“Use This Image 1178208001.” British Museum. https://ift.tt/myWsjvi. Accessed 3 Dec. 2021.

“Utterly Fascinating Theories Behind The Vanishing Roanoke Colony.” Ranker, https://ift.tt/EvnyzJp. Accessed 3 Dec. 2021.

“We Finally Have Clues to How the Lost Roanoke Colony Vanished.” Culture, 7 Aug. 2015, https://ift.tt/JsYkI13.

“What Happened to the ‘Lost Colony’ of Roanoke?” HISTORY, https://ift.tt/Pud1VaU. Accessed 3 Dec. 2021.

Yuhas, Alan. “Roanoke’s ‘Lost Colony’ Was Never Lost, New Book Says.” The New York Times, 1 Sept. 2020. NYTimes.com, https://ift.tt/Ip0Qa3k.

Has the Mystery of the ‘Lost Colony’ of Roanoke Been Solved?

Source: Kapit Pinas

0 Comments